|

The Senses Collected David

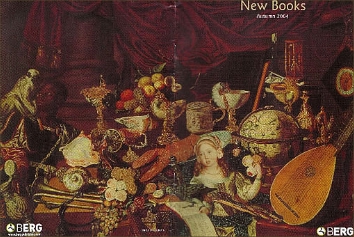

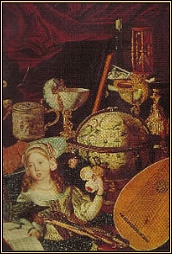

Howes This discussion of the painting known as "The Yarmouth Collection" (pictured below) is excerpted from the Introduction to Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader (Howes 2004). Click on the above image for a larger view The painting (pictured above and also reproduced on the cover of Empire of the Senses) is a remarkable depiction of a seventeenth-century collection of valuables belonging to the Earl of Yarmouth. As well as being a record of material abundance and cultural refinement, however, ‘The Yarmouth Collection’ (by an undetermined artist) is a portrait of a particular sensory order - or rather, of a number of sensory orders, which interact and challenge each other. That the painting is not just the record of the contents of a magnificent cabinet of curiosities or treasure chamber is indicated by the prominent presence of fruits and flowers. What one sees most immediately in this painting, in fact, is an empire of the senses constituted by the best the world has to offer. Fine fruits and a lobster are served up for the sense of taste. Roses and perfume bottles cater to the sense of smell. Musical instruments and a singing girl are ready to delight the ear. Intricately carved vessels and soft folds of cloth await a sensuous touch. The colorful assemblage with its glittering surfaces provides a feast for the eyes. In this microcosm earth, sea and sky are all symbolically present through representative objects and animals: minerals, plants, shells, birds. Space and time are themselves symbolized by the globe and the clock. A closer look at the painting informs us that this ‘empire of the senses’ is very much a political empire. Rich and rare sensations have been brought together from all over the world (as is suggested by the presence of the globe). Not just artefacts and plants, but also animals and humans form part of this empire. The monkey, the parrot, and the enormous lobster all speak of wealth, exoticism and dominion. The African servant and the English girl (exemplars of the subordinate social groups of non-Westerners and women) are also valuable collectibles and docile subjects in this microcosm. We see here that everything has been displaced from its original setting and brought together to form a new world order. While the arrangement of the collection in the painting might appear to be haphazard or dictated only by aesthetic concerns, the different objects and beings are in fact entwined through powerful bonds of sensuous and moral significance. The African and the monkey form a pair, mirror images, in fact, as they gaze at each other. The monkey is a customary emblem of the sense of taste and the African stands ready to serve the sense of taste with his ewer. Together they suggest the traditional trope of African lasciviousness and gluttony. The girl and the parrot form another pair. The parrot, as a symbol of chattering speech, duplicates the orality of the singing girl. This pair is suggestive of feminine loquacity. In her left hand the girl holds a bouquet of roses, making another symbolic allusion to the nature of women - attractive but insubstantial. That all the parts of the collection are at the disposal of the owner, that they are all, in a sense, dead to their own selves and living only as collectibles, is emphasized by the brilliant but lifeless lobster at the center of the painting. This empire of the senses, however, is not without its own internal critique. Neither of the human members of the collection appears content with his or her lot. Neither appears interested in the collection itself. The African is turned away from the collection, distracted, disturbed. As he looks at his fellow captive, the monkey, is he trying to reconcile a confusion of sensory worlds or to remember a former way of life? The English girl gazes wistfully beyond the collection. What is she longing for that cannot be found in this hoard of riches? The drooping roses in her left hand indicate that she cannot be preserved indefinitely, like a marble statue. Among the words written in the songbook she holds in her right hand are ‘death’s black’. The parrot which stands on the book is poised to fly away. Other elements in the painting also suggest that all is not well within the empire. The clock, watch, hourglass and smoldering candle are all reminders of mortality. While earthly treasures might be plentiful, time is running out for storing up treasures in heaven. In fact, time was also running out for the Yarmouth collection. Deep in debt the Earl was obliged to sell much of his collection, perhaps shortly after its commemorative portrait was painted.1 The papers brought together here also represent a collection, as sensorially rich and variegated as the display depicted in ‘The Yarmouth Collection’, and as full of interpretative delights and challenges. Whereas ‘The Yarmouth Collection’ is conventional in its use of sensory symbols, however, the essays here herald a revolution in the representation and analysis of culture. Notes 1. A complementary analysis of the symbolic elements of ‘The Yarmouth Collection’, along with a historical background, is offered by Robert Wenley (1991). See further Pamela Smith's 'Science and Taste' (1999) for an account of how the senses were constructed in seventeenth century Netherlands (the probable birthplace of the artist). References Classen, C. and D. Howes. 2005. The Sensescape of the Museum. In Sensible Objects, ed. E. Edwards, C. Gosden. and R. Phillips. Oxford: Berg. Howes, D. 2004. Introduction: Empires of the Senses. In Empire of the Senses, ed. D. Howes. Oxford: Berg. Smith, P.H. 1999. Science and Taste: Painting, Passions, and the New Philosophy in Seventeenth-Century Leiden. Isis 90: 421-61. Wenley, R. 1991. Robert Paston and the Yarmouth Collection. Norfolk Archaeology XLI, pt. II: 113-44 David

Howes |